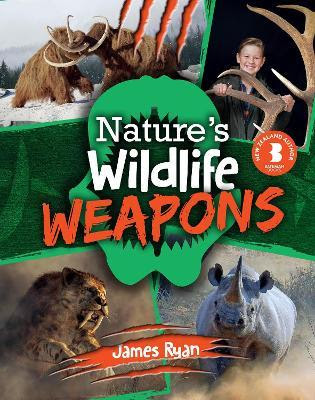

Nature’s Wildlife

Weapons (2022)

James Ryan, Bateman

32 pages, paperback, NZ $19.99

ISBN 978-1-98-853877-8

Picture young Anthony Wright, intrigued by ferns, popping

into the Auckland Museum and becoming fascinated. Now he’s Director of the Canterbury

Museum and he’s written the Introduction to Nature’s Wildlife Weapons. It’s excellent.

Picture young Trevor Agnew, intrigued by skinks and geckos, popping into the Otago Museum to get a lizard identified. Now I remain fascinated by museums and I have to write a review of Nature’s Wildlife Weapons. That’s simple. It’s excellent.

James says he wrote this book for boys and girls like

himself. He has succeeded in writing a lively and interesting introduction to

the weapon systems used by animals. His writing style is clear and natural. ‘Tusks, antlers, horns and claws are what

animals need to fight and hunt.’ Tusks,

antlers, horns and claws are also what James enjoys collecting; several illustrations

show items from his private collection. His interest has led James to research

widely, from smilodon to coconut crab, sawfish to pouākai, megalodon to

therazinosaurus.

The entertaining text is well laid out, with plenty of

intriguing section headings, such as ‘What

were the biggest claws ever?’ and ‘Deer

with tusks – weird right?’. The paragraph ‘Gross Facts’ lived up to its name by bringing together George

Washington’s dental problems and hippopotamus tusks.

James delights in the remarkable ways some creatures have

developed for hunting, defence and impressing the opposite sex. ‘They show us life close up and real.’

It is no surprise that many of these well-armed creatures

are no longer with us, while many more, like the pangolin and the rhinoceros are

now threatened with extinction. It is ironic that protective features like

horns and tusks have made some creatures vulnerable to poaching.

James has strong views on conservation and this comes

through naturally in his section on elephant tusks. ‘Ivory was once used for all kinds of things – piano keys, knife handles

and buttons. …Today there is no reason to use ivory for anything. These things

can all be made from plastic or wood.’

I especially like the way he drops quiet little jokes

into his text. ‘My mum says that my dad

has mammoth meat at the bottom of our freezer.’

James also has a good feel for history. He was delighted

to find that the drays carrying moa bones from the swamp at Pyramid Valley to

the Canterbury Museum went right past his home. He adds, ‘When the pouākai, Haast’s eagle, was alive, they circled the sky above

where I live today. And then, when they were gone, they came past one last time.’

Above all, this book radiates James’ enthusiasm for the

way our museums enable us to see some of the world’s wonders. Posing with the huge

jawbone of an extinct cave bear, he tells us that they were massive. ‘Standing on all fours this one could look a

tall man straight in the eyes. This skull has been in the Canterbury Museum

since 1874. And now we all get to see it.’

How appropriate it is that just as Nature’s Wildlife Weapons is launched, the Canterbury Museum has

brought out ‘a stampede of stuffed

specimens’ for its Fur Fangs and

Feathers special exhibition, which runs until March 27th.

Imagine the effect it is having on all us twelve year

olds.

Trevor Agnew

30 January 2022

No comments:

Post a Comment