Peter Gossage : A Talent for Communication

By Trevor Agnew

Peter Gossage died in August 2016, just before the publication of the handsome collection of his best work, Maui and Other Maori Legends (2016) Puffin NZ.

I interviewed Peter Gossage in 2005 and wrote this article which originally appeared in Magpies magazine in September 2005.

The first time I saw Peter Gossage Maui

on a plastic book-bag issued by the NZ Library Association.

Shortly afterwards I discovered his superb retellings of the Maui

legends, with their distinctive pictures. While Gossage’s books have never won

any awards – an oversight surely – they are among the best-used volumes in

school libraries. With three decades of publishing behind him, and a major

reprint just completed, it was time to talk to Peter Gossage

book-bag issued by the NZ Library Association. Shortly afterwards I discovered his superb retellings of the

book-bag issued by the NZ Library Association. Shortly afterwards I discovered his superb retellings of the

We began by discussing his schoolboy nickname, Mekon. The Eagle comic of the 1950s had superb

colour illustrations of Dan

Dare Frank Bellamy Frank Hampson Dan ’s foe was his huge-brained

green invader, the Mighty Mekon.

Did the dramatic illustrations influence a young boy growing

up in Remuera towards a career in art and graphic design? ‘Oh yes, I was always interested in art.’

Born on 22

October 1946 , in Auckland Peter Gossage Hobson Bay Kathryn

Rountree

Asked about the New Zealand A.W. Reed

‘Mum worked at ticket-writing and window display at George Courts and at Smith and Caughey, prior to

marrying,’ recalls Gossage. ‘I

remember her always encouraging me with drawing.’ He adds proudly, ‘One of my four daughters, Star went to Dunedin

Education at Victoria

Avenue Primary

School Terry McNamara

When he left Auckland Grammar in 1962, Gossage had to choose

between going to Elam

At 19, Gossage went to Canada New Zealand New Zealand

Some of his graphic work was to have far-reaching

repercussions. ‘We used to do television

programme summary captions, a graphic on a bit of cardboard, twelve inches by

nine inches, to show what programmes were on that night. I’d try to have a good

range of styles and illustrations. We

used a lot of Maori graphics.’

When retelling Maori myths and folk-tales, such as Maui or Hatupatu, writers are always faced with problems

of alternative versions, and questions of emphasis and interpretation. Gossage

takes this point seriously, exploring many accounts, ‘Sometimes I might read two or three versions of a legend, and try to

find a common denominator.’

Publishing has strict page requirements and to Gossage this

limitation can be daunting. ‘I find

that’s the most difficult part of the whole exercise – the 32 page format –

expanding or contracting the story to fit precisely. There’s got to be that

exact number of pages.’

In 1975, when Gossage began How Maui Found His Mother, he

was already planning a series of books about Maui ’s

adventures. ‘It took about ten years to

get the whole six out,’ he says, adding, ‘That big book of Reed’s [Maori Myths and Legendary Tales], that’s sort of my Bible. I used that a lot.’

Gossage is also impressed with the skill shown by the staff

at Reeds in bringing the Maui books back into

print. ‘They’ve done a good job; it’s

amazing what they can do with computers.’ He prefers not to use computers

himself. ‘I use gouache [opaque

water-colour] for my illustrations, it’s like a water-based poster paint;

gouache means body colour.’

If you examine some of his illustrations, you can just see

the brush-marks. Every figure is carefully outlined in black. ‘I call it the stained-glass technique,’

says Gossage. ‘For the first four of

those Maui books, I used to do everything with

a brush. I’d use a fine brush to do all the black outlining. It used to take

bloody hours, you know. Now I use a fine black felt pen but it’s still

time-consuming.’ For those who wonder what his pictures would look like without the outlining, see page 30 of

Pui-huia and Ponga (2004). The taiaha (long club) of the warrior in the back

row was missed.

Gossage’s art has always had a link with hotels, ‘I’ve painted quite a few murals in pubs.’

He has always enjoyed claiming that he wrote the Maui

books in bars during his lunch hours. ‘With the later books, I’d go to the pub at Newmarket

Asked about influences, Gossage says, ‘I was always struck by Lacaze’s work. [Julien Lacaze

It requires a lot of hard work to create a text that keeps

some of the poetry and magic alive, without becoming too hard for younger

readers. Gossage acknowledges that the Maui

titles weren’t just something knocked together in the pub over lunch. ‘A

writer can write a children's book in a week. It can take artist months to do

the illustrations.’

I had hopes of

Gossage confirming my belief that being a museum display artist must be a

parallel to producing the pages of a picture book – conveying information,

illustrating processes, illuminating ideas, and making people aware of things

they don’t know. Typically Gossage replies, ‘A lot of my time was taken up in changing light bulbs. Light bulbs all

over the place would keep going out.’

‘Richard Wolfe

‘How Maui

Defied the Goddess of Death’(1985) is a book where Gossage really took risks; he

is trying to educate his readers, and make them think about things like life

after death. His account doesn’t stop when Maui

is killed and leaves this world. Instead Gossage shows Maui

encountering the heavens and underworlds of Maori spiritual belief, with some

very dramatic and imaginative illustrations.

It is the Museum that Gossage

credits for his inspiration. ‘Well, I was

working in the Museum at the time and I had a key to the Reserved Book Room,

where there was all sorts of stuff recorded from tohunga over a century or so

ago. There I found these charts of the Maori idea of the cosmos, the heavens

and the underworld. And I’d never heard of this supreme being, Rehua. She’s the

Goddess of Kindness and Healing. They never told us about her at school.’

Gossage adds, ‘I put

that little author’s note at the back of How Maui

Defied the Goddess of Death just to cover myself. I said that the traditional Maui saga ends when Maui

is killed by the goddess of death. What happens next in the book is set in “the

Maori concept of the cosmos, heavens and underworlds” Just to cover myself.’

He said, “Why don’t

you Pakeha leave our culture alone?”

But

that was the only occasion.’

In their original versions, the

last four of the Maui books had dual English

and Maori texts. Why was Mirimiri

Penfold Maui saga remains

open.

‘They’re all adults now,’ says Gossage, admitting that he himself is

the grumpy artist on page 19 who tells the children, ‘And keep out of my

paints. They cost a fortune.’

Since completing the Maui

saga twenty years ago, Gossage has mainly produced retellings of Maori myths,

such as Hatupatu, Hinemoa and Tutanekei, and Pania of the Reef, keeping the

same hard-line, stylised illustrations as the Maui

books. This gives them a unity with his sadly under-rated introductory history

book, New Zealand

Gossage agrees that this was a deliberate decision on his

part, again referring to Russell

Clark

In 1985, Gossage published The Black Knight, a medieval tale

about tolerance with a twist. He had hoped to produce a series. What happened?

‘The Black Knight got published,’

says Gossage, ‘but I couldn’t find

anybody to follow it up. I had three stories written’. He adds wryly, ‘That’s why I do Maori legends – because

they’re the ones that publishers want, and they’re the ones that sell.’

‘I’ve had a few

rejections over the years. You might notice, in the last Maui

book, the space invaders pictures.’ On page13 of How Maui defied the

Goddess of Death (1985), Maui encounters a

wave of electronic images, from a space invaders game, as he passes into the

Underworld.

Gossage’s next project was developing the space invaders

theme into a book, The Boy Who Beat the Space Invaders. The contract was signed

and the work done but Lansdowne changed directors, and ‘the numbers didn’t add up’ so the project was cancelled. Gossage, however, retains the pictures and the

copyright. ‘It’s about a boy playing an

electronic game. As he plays, what he can see on the screen is tracking across

the bottom of each page. Meanwhile the game is affecting his ancestors in the

past and his descendants in the future.’

Will we see The Boy Who Beat the Space Invaders some day?

Gossage is as non-committal as ever.

‘Reeds have shown a

bit of interest in it.’

About his earnings, Gossage is philosophical. He has to be.

‘They print about 3000 copies a time of

these books, and I think you get about 14% of the profits as royalties,’ he

says. ‘If I got paid by the hour, I’d be

rich.’ The disparity between the amount of work involved in telling the

stories and illustrating them clearly irks him. ‘They split it 50:50 and I think that’s totally unfair.’

At the same time, he knows of an advantage that artists

hold. ‘But it’s a two-edged sword. You do

retain copyright of the art-work, and the art-work itself. Often at exhibitions I’ve sold the original

art-work for more than I get for the book.’ He laughs and adds, ‘The work is rewarding. Ah yes.’

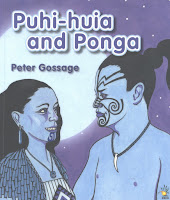

‘That couple on the cover there - the models - they’re a couple of

patients at the hospital. I took photos of them, blew the photos up, and

xeroxed and traced them off. I think all of that book was done in the hospital,

which is the reason it’s not quite up to the standard of the other ones.’

He may be right but Puhi-Huia and Ponga also contains some technically

demanding moonlight scenes, among his best work.

Thirty years after he first painted a moko on the face of

the moon, Gossage is doing it once more. At his publisher’s suggestion, he’s

working on a version of Rona and the Moon

‘I was reading the

version in the big A. W. Reed book,’ Gossage says, laughing. ‘And Rona was carrying on with a neighbour

and her husband cut his genitals off and cooked them, and tried to get her to

eat them. So I said, “I’m not doing a children’s book on that” So, I’ve toned

it down a bit.’

Just out of hospital, Gossage is finding again just how

physically demanding painting can be, with its need for concentration and

attention to detail. ‘I’ve spent the last

few days doing the first double-page spread for this latest book [Rona and

the Moon] and it’s been so arduous.’

Are there compensations?

‘I quite enjoy it,

yeah.’

Predictably, Gossage rejects praise for his do-it-yourself model volcanoes, supplied at the back of his latest book,

In fact he has every reason to be proud. With his books in

every school and library in New

Zealand Peter

Gossage

‘Oh, pretty good.’

A Peter

Gossage Booklist

How How

The Fish of

How

How

How

The Black Knight (1985)

Hatupatu and the Bird Woman (1989)

Tahu, Ra and the Taniwha (1992)

In the Beginning (2001)

Hinemoa and Tutanekai (2002)

Pania of the Reef (2003)

Puhi-huia and Ponga (2004)

The Battling Mountains (2005)

No comments:

Post a Comment