‘Nothing with pictures. No pictures!’ by Trevor Agnew

We all know that books for young people are important. Except that some people seem to think that picture books are just an optional extra. They’re for toddlers to chew on – sometimes literally – until they get down to real reading. I still remember a fellow teacher who brought his classes into the school library to borrow books, shouting his final instruction, ‘Nothing with pictures. No pictures.’Casting my mind back, I can’t recall picture books in my childhood. The wicker baskets from the School Library Service that arrived periodically at Sawyers Bay School had plenty of well-illustrated stories and non-fiction books but no picture books. Avis Acres passed us by, un-noticed. Any pictures we saw were in the School Journals (Russell Clarke) or the school set of Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopaedia.

Seven decades on, two framed pictures face me as I work – original book illustrations painted by artists whose work is both widely loved and under-appreciated. Jenny Cooper’s creation is the double-page spread of the madly dancing duck from her version of There’s a Hole in my Bucket. It has a background of tiny blades of grass, each individually hand-painted.

From There’s a Hole in my Bucket by Jenny Cooper

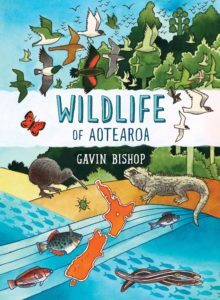

The delight I feel in seeing these pictures every day is matched by the pleasure I feel every time I unwrap a new parcel of review copies. While writing this, I unpacked Gavin Bishop’s Wildlife of Aotearoa, which uses five eels to tell the story of our natural history. It’s not just that Gavin’s designs are striking; I’m also amazed at people’s response to his art. I’m part of a Christchurch group, organised by Painted Stories, who gather regularly to discuss picture books. When I brought out Wildlife of Aotearoa, there was an audible gasp from the others and they reached out with excitement and anticipation, then turned each page with satisfied exclamations. What impressed them was the way the illustrations drew them into each topic.

The delight I feel in seeing these pictures every day is matched by the pleasure I feel every time I unwrap a new parcel of review copies. While writing this, I unpacked Gavin Bishop’s Wildlife of Aotearoa, which uses five eels to tell the story of our natural history. It’s not just that Gavin’s designs are striking; I’m also amazed at people’s response to his art. I’m part of a Christchurch group, organised by Painted Stories, who gather regularly to discuss picture books. When I brought out Wildlife of Aotearoa, there was an audible gasp from the others and they reached out with excitement and anticipation, then turned each page with satisfied exclamations. What impressed them was the way the illustrations drew them into each topic.(All of Gavin’s picture books have this effect. When I showed an elderly cousin Cook’s Cook, she went straight out and bought her own copy!)

Recently I donated several boxes of books to a local primary school, where a large number of the pupils speak other languages and are learning English. The volunteers who help with the reading programme know the value of good books. (And they know how dud books can turn kids off.) One was rapt about The Lazy Friend by Ronan Badel, a picture book about a dozing sloth who has to be rescued by his forest friends when his tree is chopped down. Since this book has no words at all, a hesitant young lad found himself telling the story as they went along, excitedly decoding each picture and putting it into his own words. Not only was he rapidly gaining in confidence and enthusiasm but he was also seeing books as a pleasurable, non-threatening experience.

Some picture books go straight to children’s deepest emotions, like Kate Wilkinson’s powerfully poignant illustrations for Elizabeth Pulford’s Finding Monkey Moon. Every child has a favourite toy and every parent dreads the anguish when that toy is mislaid. Michael and his father (the only two characters in the book) realise that a beloved toy monkey is missing at bedtime. The pictures in Finding Monkey Moon bring comfort and reassurance as the pair search the playground in the wintry darkness. Michael sits comfortably on his father’s shoulders, as they pass through the dark trees. When their search succeeds, Michael carries his toy monkey home on his shoulders, just as his father carried him.

(The pictures have their own back story. Kate discovered she was pregnant with twins the day she got the contract to illustrate the book. She soon had trouble reaching the drawing table over her bump. The twins were three by publication and she was able to read the book to them.)

Our seven grandchildren have always proved useful guides to reader ages and interest. It is fascinating to see which books hold them and which are quickly discarded. The winner of the popularity stakes, so far, is That’s Not a Hippopotamus, with its combination of Juliette MacIver’s rhymes and Sarah Davis’s meticulously crafted illustrations. Young readers literally identify themselves as one of the class rampaging through the zoo, seeking a hippo. Sarah Davis not only created 18 distinct characters but also found dozens of ways of (almost) concealing a hippopotamus from them. The joy for the young reader is that they are let in on the joke; the teacher can’t spot the hippo but the reader (and Liam) can, so every turn of the page is hilarious.

From Guji-Guji by Chih-Yuan Chen

As their most beloved picture book, my children and grandchildren chose The Monster at the End of the Book, where Grover (of Sesame Street) implores them not to turn the page. Turning the page is a gleeful act of defiance. The joke is that the monster is really loveable Grover. That doesn’t stop the regular demands for another reading. And another. Familiarity breeds contentment.

Of course pictures open up fresh perspectives, and help us to see things we might never have imagined. The best picture books create mindscapes which let the young reader experience their own story. This is another reason why so many of them enjoy reading the same book over and over. The experience gives them a strong idea of story structure and conclusion.

New Zealand children today have a steady flow of picture books that offer them insights into their own

Detail from Mr Muggs the Library Cat by Dave Gunson

Many of the reasons that picture books are important are beautifully summed up in Dave Gunson’s colourful tribute to the joy of reading, Mr Muggs the Library Cat. I was captivated by its richly-coloured literary romps before I received a cryptic e-mail from the artist. It said, “Look in the fridge.”

Picture books are great.

Trevor Agnew is a writer, researcher, reviewer and passionate advocate for children’s and young adult literature, especially New Zealand books. You can find Trevor at http://agnewreading.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment